Tech-Talks BREGENZ - Prof. Christian Cajochen, Univ. Basel, Head of Center of Chronobiology

Human Centric Lighting has become a catchphrase used by industry and the press. But the press has also started reporting that research emphasizes the danger of LED lighting in connection to our health and has coined the term “Blue Light Hazard”. These claims have caused confusion amongst end users and throughout the lighting community. Prof. Christian Cajochen, Head of the Centre for Chronobiology at the University of Basel - an expert on this topic - held a lecture at the LpS 2016 entitled “Light Beyond Vision”. Afterwards, LED professional seized the opportunity to talk to him personally and get some in-depth information about the risks and benefits of LED lighting.

LED professional: I would like to start by saying that we are not only interested in technologies. We want to know how technologies should be applied correctly to be of value to people health-wise and for their well-being. I know that you have a strong focus on cognition, circadian rhythm and sleep and the influence of light on different physiological aspects. So my question is, how do you see the LED? Do you think it’s applied correctly? Can it be improved?

Christian Cajochen: Chrono-biologists have been interested in light for the past 50 years, well before the LED era, because light is the most important zeitgeber for circadian rhythms of our inner clock. Now with the progress in technology - especially LED technology - it’s a wonderful way to create new light solutions. With new technologies you have more freedom that you can use or misuse. There is no good or bad way of how to apply this new technology. Having more technological possibilities gives you more possibilities to improve the light. With every new technology you can also do it the wrong way - but we learn a lot. We are still learning how to apply LED technology in human settings. But my personal view is that it is a great tool.

We know now that wavelength of light is important for different aspects of physiology in humans. With different light sources or different nanometers you can induce different responses like alertness. So the person is more awake, or you can go in the other direction and induce sleep. It really depends on what you are looking for. You can tailor your LED according to what your questions are. And that’s really new.

LED professional: Do you think that the industry understands about the biological and physiological effects of light?

Christian Cajochen: Actually, I’m very happy to be here by invitation of the industry. And because they invited me, I believe that they are becoming aware of what we call the non-visual effects of light. These are all the effects of light that are not related to vision but rather to other things like sleep and circadian rhythms. The industry wants solutions from us, but really, it’s too early. We are still not sure amongst ourselves and the industry is already asking for regulations and norms. We can give them broad recommendations but it’s too early for things like percentages. We’re still in the experimental phase. Although I think we need to move out of the laboratory quite soon and look at real life situations. For example, we’d like to investigate different light solutions with 500 people that work in a telecommunications company and find out what type of light they like in terms of well being, cognitive performance and also sleep.

LED professional: Can you recommend specific solutions right now?

Christian Cajochen: I think it’s a bit too early. I’m a bit reluctant to say “…you need to have this type of light for a certain solution …” because there are no simple solutions so far. And that makes it a bit complicated. It’s the intensity and the wavelength and the timing of light that are important. Which means you have three different degrees of freedom you can manipulate. It’s not just a pill you can give a patient and say “That’s good for you.” Of course that makes it more interesting and more innovative but harder to give simple recommendations.

LED professional: Could you give us an example of your research? You said it’s mainly experimental research - so how are the experiments set up?

Christian Cajochen: We study people in controlled laboratory conditions. A typical set-up would be that they come to our laboratory and they spend one week there in our setting. They have an apartment where things like humidity, temperature and, of course, lighting are precisely controlled. We do very intensive physiological monitoring of the people; we monitor their heart rate, brain activity, hormonal changes and cognition (they have to do tests). They spend one week there under, let’s say, a dynamic LED daylight simulation compared against normal office lighting.

LED professional: So you’re saying that they don’t stay under controlled conditions for 8 hours and then go home; they stay there 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Is that correct?

Christian Cajochen: That’s right. We want to prove whether this light regime, per se, is working under controlled conditions without any disturbance. That’s the first question and then if you can say yes, we see an effect, then you can gradually move to more realistic settings. And then you may discover that our lab data is wrong. But, so far, we have been able to confirm the effects mostly, also in settings that aren’t so controlled.

It’s important to have control studies in the lab, but it’s also important to have studies that are outside the labs. I think, for the industry, what counts is outside and not in the lab. What I talked about before is a typical setting in our lab. But we also do semi-realistic settings so that people can go home at night or we are adapting the light or we are just measuring the light that they perceive during the day. The light history is also very important.

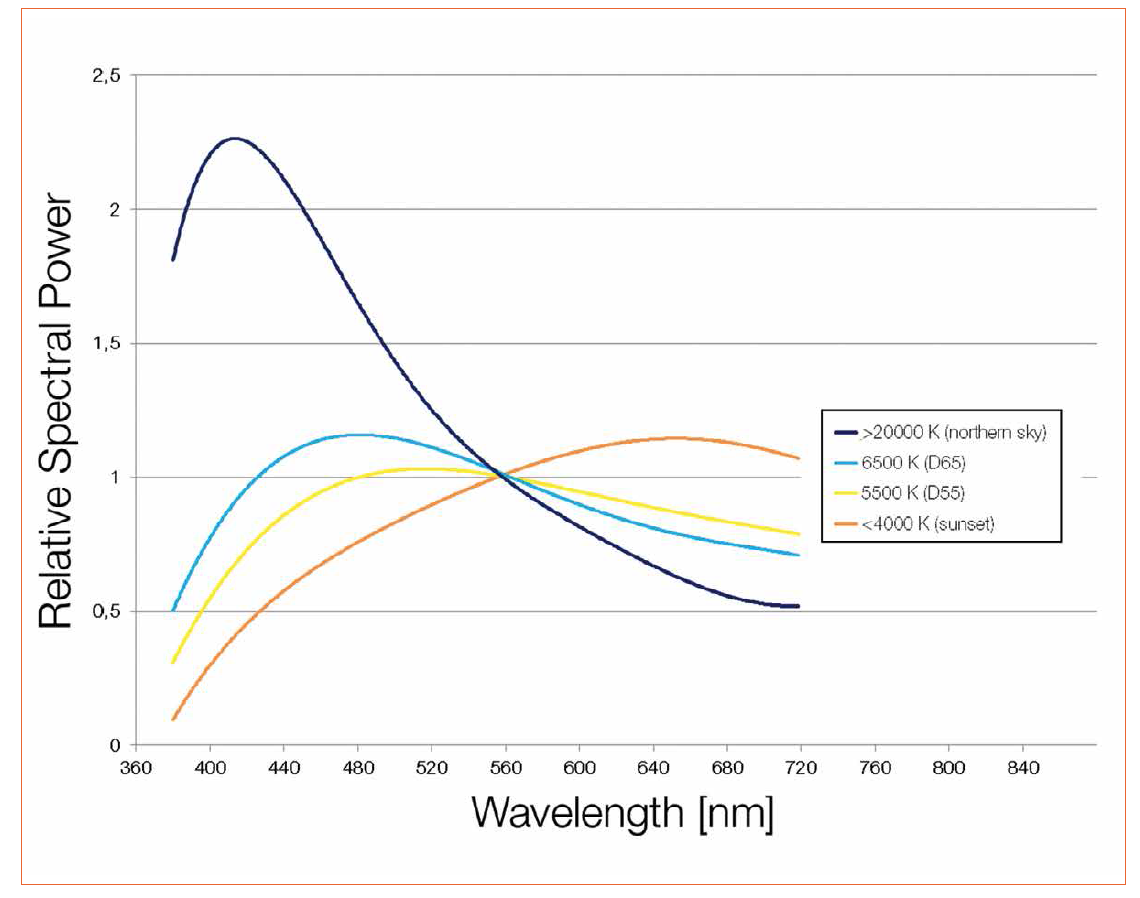

Natural sunlight is often regarded to be the optimal light source because of our evolution. The spectral distribution of sunlight depends on many different factors like daytime or weather conditions. The simplified graph shows how the spectral distribution of sunlight varies during the day. LEDs can be tailored to emulate these situations. Advanced HCL systems even can dynamically adapt the light closely to these spectra

Natural sunlight is often regarded to be the optimal light source because of our evolution. The spectral distribution of sunlight depends on many different factors like daytime or weather conditions. The simplified graph shows how the spectral distribution of sunlight varies during the day. LEDs can be tailored to emulate these situations. Advanced HCL systems even can dynamically adapt the light closely to these spectra

LED professional: Did you ever consider the influence of the history just before they go to your laboratory? Is there a difference between people that come to the lab in the spring and people who come in the winter?

Christian Cajochen: That’s a very important and interesting question. It’s a bit difficult to investigate because you need people to come in in different seasons. It has been shown that prior light or dark makes a difference. So if you come into an experiment from a sunny day like today and we’re looking at light and motivation, the results would be different than if you came in on a dark winter morning. We try to assess these influences so what we do right now is we have a dark adaptation that lasts for a half hour for everyone when they come in. We think that a half hour is enough, but we don’t know.

Right now we’re doing a study looking at different color temperatures and motivation. This is motivation measured by an autonomic nervous system task. It’s sensitive and when they come in in the morning, we see a clear relationship to color temperature. But in the afternoon, when they’ve already had some different light exposures, we still see it, but it’s not as obvious. So the light / dark histories are very important.

LED professional: What types of tests do you do on the people?

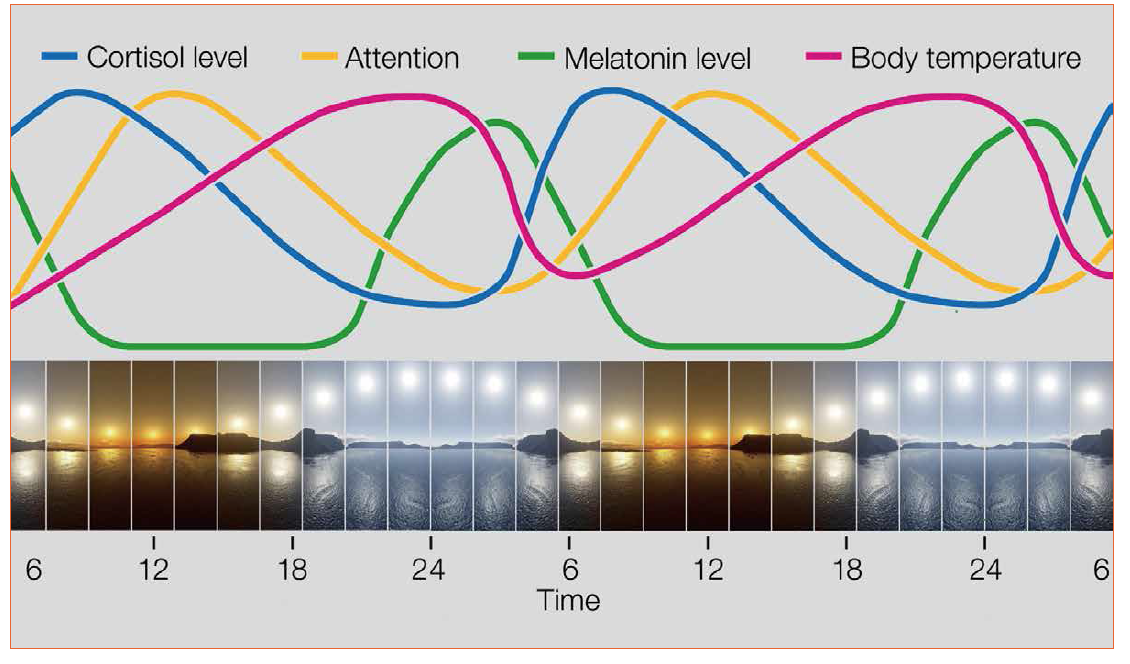

Christian Cajochen: We call the tests “Intensive Physiological and Psychological Monitoring”. The people are wired up with 20 to 30 cables that measure brain activity, heart activity, galvanic skin response, skin temperature and the physiology behind it. We also do MRI scans sometimes with different light sources. That’s the physiological part. Then we do psychology. The people do cognitive performance and reaction time tasks, emotional memory, and creativity. We measure creativity by having them draw pictures and the psychologists in my group have an algorithm to analyze creativity. And we also measure hormone levels in the blood like melatonin, or cortisol for stress reactions. Sometimes we measure more things and sometimes less, it depends on the money we have. Some of these essays are very expensive and, so far, the industry hasn’t been interested in sponsoring us.

LED professional: We know that light influences the level of melatonin in the blood but I don’t know about any studies that show that light directly influences other hormones.

Christian Cajochen: Melatonin is the hormone to measure the position of your inner clock. You can suppress melatonin and it also shifts with the light. That is the standard measurement.

Nobody looks at other hormones in a very consistent way. Melatonin is the only hormone where we know the exact neuro-pathway. But cortisol also seems to be an interesting hormone to look at. If you have light in the morning it looks like the cortisol is increased but if you give it at night it looks like you can reduce cortisol levels. So it’s not very clear there. Cortisol is indirectly influenced by other brain centers because it speaks to the adrenal gland and so it can influence cortisol levels.

LED professional: At the workshop you held, Professor Anya Hurlbert presented a slide that showed, that the fact people knowing they were being experimented on made a difference in the results.

It has been known for a while that light affects the circadian rhythm and hormonal balance of humans. But details on just how our health is affected still need to be clarified. Now that LEDs are spectrally tunable it is relatively simple to adapt and optimize them to reduce risks and improve well-being

It has been known for a while that light affects the circadian rhythm and hormonal balance of humans. But details on just how our health is affected still need to be clarified. Now that LEDs are spectrally tunable it is relatively simple to adapt and optimize them to reduce risks and improve well-being

Christian Cajochen: What she showed was that she exposed people to different light levels, like we do, but she sent them home afterwards. She didn’t control before - and since they knew they were a part of an experiment they were a little excited. After the experiment they slept less - but one reason for this could be that they were exposed to light in the evening, which delayed their circadian rhythm. Professor Hurlbert is not a circadian biologist - she’s more into vision and looks at the visual aspects.

LED professional: So there are quite a lot of factors that you have to take into account when you set up the laboratory for an experiment.

Christian Cajochen: Yes, and we are very strict. We have to separate all these influences because humans are very complex. You have to be very careful whom you pick. Some people think that certain light is good for the soul and another light isn’t. So we also have to watch out for that type of thing.

LED professional: Does the goal of the experiment also influence the people taking part?

Christian Cajochen: Yes and no. You have to tell them the setup of the experiment otherwise you won’t get approval - but we then just tell them that we are going to test different wave lengths and we don’t know which ones will influence their sleep. Recently we have had people come to the lab and tell us that they know the effects of blue. And then we have a bit of a problem. They can’t influence the melatonin levels but they could, if they wanted to, screw up certain tests. I personally like the people that just do it for the money because they don’t have an agenda and they just deliver the data.

LED professional: If we talk about Human Centric Lighting, I guess the most important thing is that light shouldn’t have a negative influence on your health. There are two other topics that I’d like to hear your opinion on, though. The first one is blue light and the concerns that it could cause cancer. The other topic is flicker.

Christian Cajochen: Well, I can’t give you an opinion about flicker because I’m not an expert on that topic - I didn’t even know that LEDs flicker.

LED professional: Normally, it isn’t visible, but they do flicker.

Christian Cajochen: It has never been an issue for us. I’m not aware of the problem. But I do know something about blue light or “light at night” - LAN effects and Breast Cancer. There is some physiological evidence that shows women, or night shift workers in general, are more at risk for breast cancer. The WHO has proclaimed that shift work - not light at night - is potentially carcinogenic. It may not only be related to light; it may also be related to the shift in the circadian rhythm. The shift worker works in the wrong circadian time window. I’m very critical about it because there is the fact that it reduces your melatonin level and melatonin scavenges for free radicals. It’s a logical mechanism but it hasn’t been proved without a doubt so far. All that has been seen is that shift workers have a higher risk for cancer.

I know that in Israel, for example, they are against LEDs and blue LEDs because they say they cause breast cancer but so far I think the evidence is for epidemiological data and not for experimental data.

LED professional: So if I understand you correctly, you’re saying that it’s not the LED itself that is causing the cancer, but rather the shifting of the circadian rhythm.

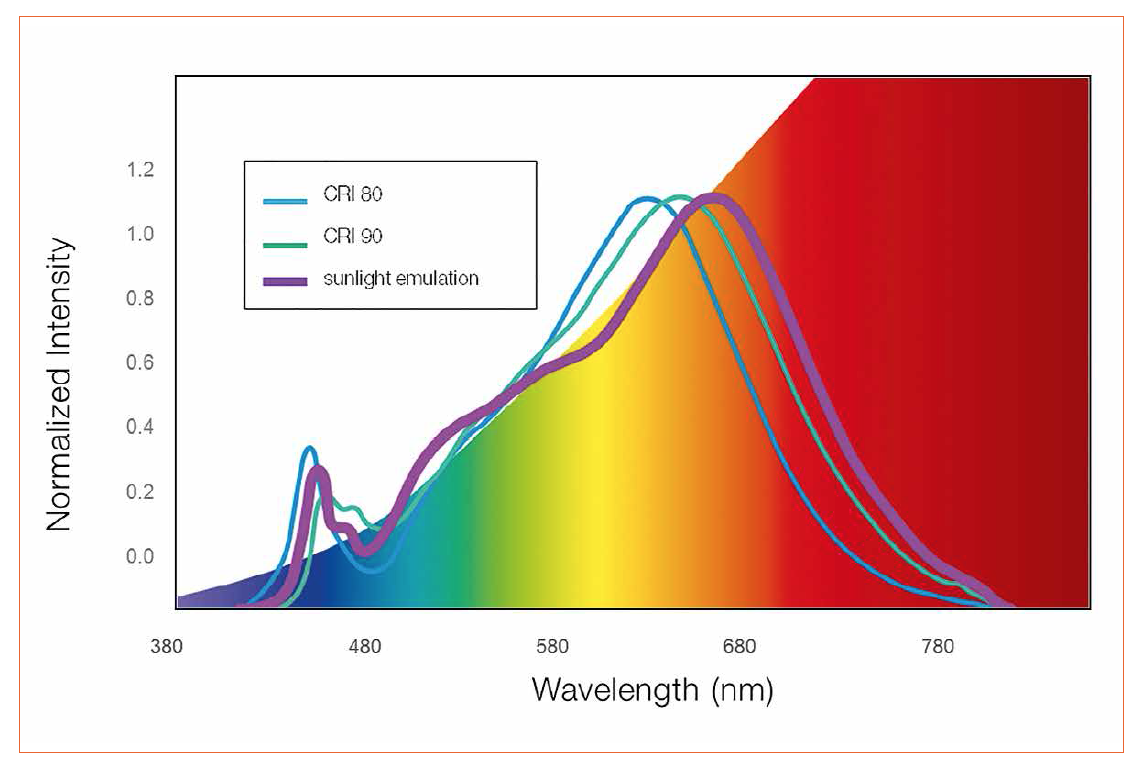

One of the latest trends in manufacturing LEDs is the emulation of sunlight at different CCTs

One of the latest trends in manufacturing LEDs is the emulation of sunlight at different CCTs

Christian Cajochen: It’s a mixed effect. They receive the light at nighttime at the wrong circadian phase, which is not good, per se. And their activities have been shifted. I have some ideas how we could manage light during the night that would improve performance. I can’t say that it would prevent cancer because we don’t know what really causes the cancer. In my opinion, the only good control would be a blind woman that works night shift but that is not possible. However, there is some evidence that blind women are less likely to get breast cancer than women who can see.

So appropriate light at the appropriate time with the appropriate spectrum would be the ideal situation. If you don’t have that, it interferes with your health. On the other hand, noise at night is also not good for you.

LED professional: Do you think that in the near future there will be studies that show how to design a “good light”?

Christian Cajochen: We are a part of a European project called “Human Centric Lighting” and we are trying to make recommendations for workplaces, educational institutes and hospitals as well as domestic domains and street lighting - whereby street lighting is more difficult. But we have come up with some agreements based on data in peer reviewed journals and we also developed the tool that I presented today that you can download. It’s an Excel file that you can put in your light source - the color temperature, the intensity and then you calculate the melanopic daylight equivalent. So you know that if you install a certain light bulb it will be more or less activating.

And we can also give some recommendations. I think it’s the right time to give some general recommendations. We can’t yet say, “…if you want this result you have to install that light”, but we can give some general recommendations. Whether the industry will follow the recommendations or not remains to be seen. I’m a little pessimistic about that because I don’t believe the industry will change things unless they see that there will be a profit.

LED professional: That would have been my next question!

Christian Cajochen: Well, maybe I’m a little too pessimistic because we have gotten some positive feedback from Telecom in Germany. They said they might try some of our recommendations and also the Swiss retail companies, Migros and COOP, for example. They have a lot of workers working underground with no access to daylight and because of our recommendations they have given their workers 2 extra breaks to go up and take in some daylight. These breaks are paid so it costs the company a lot of money. We are looking for an LED solution that would mimic sunlight, which would mean the companies wouldn’t have to pay for the extra breaks anymore. It’s also a political issue and I think the industry might consider changing their lights if there is political pressure.

LED professional: We talked about light at night. What about light during the day? Sometimes people don’t have the correct light throughout the day.

Christian Cajochen: In my opinion it would be good to bring out results to people who work during the day but don’t have access to daylight. There are many people that work without daylight and that’s where I think we should try to apply some of our recommendations to see whether they help or not.

LED professional: You spoke about mimicking daylight. Today everyone is talking about certain cycles in color temperature and intensity. However, if we look at real daylight, it’s completely different. A normal day would have a blue hour in the morning with color temperatures up to 20,000 K and then it falls rapidly and the color temperature stays between 5,000 - 7,000 K for the rest of the day. How do you think we could mimic sunlight correctly?

Christian Cajochen: The word mimic is used very loosely. In our office, for example, we have a dawn and dusk simulation but depending on the distance from the equator, it would be different. There is a gradual change, also in the color temperature. Of course it stays stabile during the day and then it goes down again. But the thing is we don’t know if mimicking daylight works. There are no studies proving that a dynamic light is better than a static light. There was a study ten years ago where they put in 7,000 K lights. People hated it at the beginning but after a few weeks they didn’t want to go back to the old light. Performance was better even though the light was awful.

This is the reason that we have implemented a virtual sky in our lab. We have panels from the Fraunhofer Institute that help us simulate a more natural environment with clouds passing by and the color temperature between 4,000 K and 6,000 K but in a more dynamic way. We just started to test three variations last week. A dynamic sky, a static sky and a traditional office setting. It’s a very cumbersome experiment so we will have to see what happens.

LED professional: Are there any other things that have to be considered if we look at the natural change of daylight?

Christian Cajochen: Yes, it’s the duration of light, the photo periodic changes. For instance, we have patients in the psychiatric clinic that I work in that are very sensitive to the reduction of day length in fall and winter. These people develop what is called Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD). A lot of people, including some psychiatrists, don’t believe it, but it’s more than just the “winter blues.” These people gain weight and feel miserable - and as soon as you can extend the light duration, you can help them. When it’s dark in the morning and dark in the evening, some people just don’t feel good.

LED professional: Do you think that it’s better to extend the duration of light instead of giving people “light therapy”, a high dose of light during the day?

Christian Cajochen: Extending the duration is next to impossible, so we still treat those patients with light in the morning. You don’t have to give them 10,000 Lux anymore - if you blue enrich the light, you can treat them with lower illuminances. It’s a treatment of choice and it’s a lot to ask someone to sit in front of a light for a half hour every morning. Most people just prefer to take a pill - an anti-depressant. But if you compare the pills to the light - they aren’t better; in fact, the light treatment has been shown to be superior in some cases. So I’m a big fan of light therapy. It works in 70% of the patients - which is the same success rate as anti-depressants. In Switzerland doctors know about it and the Light Box is covered by our health insurance.

LED professional: Thank you very much for this very interesting interview. We are curious as to how “Human Centric Lighting” will develop over the next few years and look forward to hearing about the results from your research.

Christian Cajochen: Thank you.

About Prof. Christian Cajochen

He heads the Centre for Chronobiology at the University of Basel. He received his Ph.D. in natural sciences from the ETH in Zürich, Switzerland, followed by a 3-year postdoctoral stay at the Harvard Medical School in Boston, USA. His major research interests include investigative work on the influence of light on human cognition, circadian rhythms and sleep, circadian related disturbances in psychiatric disorders, and age-related changes in the circadian regulation of sleep and neurobehavioral performance. He holds a number of honors and has authored more than 100 original papers and reviews throughout his career.