Tech-Talks BREGENZ - Ken Munro, Partner & Founder, Pen Test Partners

Today, hardly a day goes by that we don’t hear about security breaches, hacker attacks or comprimized data; often as a result of insufficient security measures. IoT does not really improve this situation and it is therefore necessary for the industry to take this threat seriously. This is especially true for the lighting industry, whose aim is to become the IoT enabler. Ken Munro, founder and partner at Pen Test Partners, is an ethical hacker whose passion is to hack any technical product he can get his hands on. Unfortunately, he succeeds way to often. LED professional talked with him about ethical hacking, where he sees the risks in various products, where the risks are hidden and what can be done to minimize them.

LED professional: Thank you for coming to the Tech Talk Bregenz. We’re really interested to hear more about network security and data privacy in the context of the Internet of Things (IoT). We’re seeing nodes on the network proliferate and - from what we saw in your presentation - those networks are being exposed to attack through our failure to configure these devices correctly or deploy them securely. But before we go into details, can you tell us a little about yourself and your company?

Ken Munro: I work for a company called Pen Test Partners and we specialise in the security of the IoT. That grew out of our extensive experience in working on embedded control systems found in industrial utilities like electrical companies and water companies, where these systems are used to manage production processes to control supply. These are very important systems: if they go wrong, the power goes out. Over time, these systems were connected to allow utility providers to control their production facilities from the other side of the country or the other side of the world resulting in sensor-based networks. Now we’re seeing the replication of that in the IoT.

Just to be clear, the IoT by itself is fine. The technology offers us unprecedented convenience and control. We can warm our house or our car when we need to. Monitor the safety of our homes and provide access remotely. And in the medical arena we can better manage patients with longrange diagnostics to check on pace makers or blood pressure monitors.

It’s when we connect these insecure devices to the Internet that we can run into problems with hackers quick to exploit vulnerabilities. Fortunately there are many companies, like ourselves, who are researching, disclosing and publishing issues. Sometimes the manufacturer listens and sometimes they don’t. In fact, more often than not - they don’t. And then we have to talk about it to the public - because if we don’t, the problem doesn’t change.

The flaws we find vary. It could be that the manufacturer forgot to implement encryption so there is no SSL or TLS so it’s easy to intercept the traffic. Or maybe it’s problems with the API which determines how you control the device from your smart phone or via the cloud and that can see you able to control all those devices. Or a hacker may seek to seize control of a bed of devices, to steal personal data or to cause havoc through maliciously switching off services.

One that we spend a lot of time investigating is firmware security on the IoT hardware. If this hasn’t been written securely and the chip hasn’t been secured either, the hacker can extract the firmware and reverse engineer that. Often we discover that we can hack every component of the system through to the device, the manufacturer, the hosting company of the API, you, your customer - everything - because the firmware is not written properly.

Besides "his electrical IoT kettle", the doll, Cayle, is one of Ken Munro’s preferred examples of vulnerable products. In the meantime Germany has stopped importing her

Besides "his electrical IoT kettle", the doll, Cayle, is one of Ken Munro’s preferred examples of vulnerable products. In the meantime Germany has stopped importing her

LED professional: I’d just like to clarify one point: In general we are always talking about hacking. But hacking, per se, is not the criminal act of corrupting or damaging something. Could you just explain exactly what hacking is?

Ken Munro: The term hacking doesn’t apply to what many people think. Hacking is playing around or tinkering. The term comes from years ago when people would hack a device to make it do something different or hack together technology. It’s only recently that it’s been associated with malicious activity over computer systems. What we provide is ethical hacking: a hacking service that is done in a controlled manner where the intent is “good”. So you could say that the crux of the matter is the intent. If hackers have the wrong intent and try to damage you, they are the people you should be worried about. But there are many ethical - or “White Hat Hackers” - out there whose aim is to improve security by spreading awareness. As a company, you can engage them to test and evaluate your security. Some will find flaws and tell you about it for free. Sometimes they’ll want a reward - we call it a bug bounty - but by and large, they are motivated to do the right thing.

![Encryption and data security companies monitor data breaches and publish their findings on a regular basis. The info-graphics (Credits: Gemalto [1]), speaks for itself and leads to the conclusion that making IoT devices as secure as possible is paramount Encryption and data security companies monitor data breaches and publish their findings on a regular basis. The info-graphics (Credits: Gemalto [1]), speaks for itself and leads to the conclusion that making IoT devices as secure as possible is paramount](https://www.led-professional.com/media/resources-1_articles_tech-talks-bregenz-ken-munro-partner-founder-pen-test-partners_breach-level-index-infographic-2017-gemalto-encryption.jpg/@@images/image-1280-b3a3a95ba9796332d8d6b3097827c923.jpeg) Encryption and data security companies monitor data breaches and publish their findings on a regular basis. The info-graphics (Credits: Gemalto [1]), speaks for itself and leads to the conclusion that making IoT devices as secure as possible is paramount

Encryption and data security companies monitor data breaches and publish their findings on a regular basis. The info-graphics (Credits: Gemalto [1]), speaks for itself and leads to the conclusion that making IoT devices as secure as possible is paramount

LED professional: And to really get an idea of the importance of the safety and security issues: Could you give us a short history of how it has changed over the years?

Ken Munro: The biggest step change has been the connection of very sensitive systems, or lots of less important systems, to the Internet. Initially, the Internet was just a lot of connected computers. Sensitive systems were all safely tucked away on protected networks. Take, for example, the control system of a nuclear power plant. This would have been isolated on a dedicated network which may have used obscure protocols as opposed to HTML. Nowadays, even highly specialised organisations want to connect their systems to the Internet to gain the advantages of remote access and they think setting them up privately so they can only connect from the power plant to the control room, to the corporate HQ is sufficiently secure. But along the way, mistakes can be made. Imagine if the telemetry system governing a nuclear power station were to be interrupted, threatening control of the system. That is as bad as it gets and this genuinely happens.

There is an excellent search engine called Shodan (shodanhq.com) for Internet connected devices where you can locate industrial controllers for hydroelectric power stations, electricity generating plants, production systems control for production lines: they’re all on the Internet and are discoverable when they shouldn’t be! The compromise of these devices can lead to devastating consequences. If you were to lose access to the Industrial Control System of a nuclear power station, there could be severe consequences. But few people realise that, collectively, the compromise of millions of IoT devices can also power large scale attacks. Imagine if I had control of one million smart thermostats or ten million smart light bulbs or a thousand smart vehicles. What if I could make all of those IoT devices start making requests against one system? If they’re instructed to simultaneously “Connect to google” or “Connect to a DNS provider” or “Connect to a social network” that can create a denial of service attack. We caught a distributor denial of service attack or a “DDoS” last year and it took FaceBook and various other social networks off the Internet. And that is the risk of not getting IoT right. You might think “It’s just my light bulb” or “It’s just my thermostat” but when in their millions, those devices can cause a huge amount of damage.

LED professional: Is it always the device itself or can it also be caused by the implementation? For example, if I have my light bulb in my system connected to my private network with Internet access, am I personally accountable because my Internet connection is not secure?

Ken Munro: Some responsibility does rest with the user. So it’s very important to make sure that your password is secure. The Wi-Fi key should be changed so that it’s different to the original one shown on the back of the router. The mobile app you use to control your smart lightbulb needs to be unique and set by you. If it’s too simple or it’s a password you use somewhere else you’ll be easier to hack. It has to be strong, by which I mean long and complicated. A password manager can help generate and store these passwords for you and you never have to remember it. It’s a little app that runs on your phone or your computer and all you have to do is copy and paste your password or auto-populate the password on that app.

LED professional: That’s a good tip for everyone! But tell me, what can a hacker do once he has control of your device? Yes they can switch it on or off or locking and unlock your door, observe your habits or steal your personal data and post it online or attack a system. But are there other ways that the devices can be misused?

Ken Munro: Yes, very much so. But let’s start with the first one. What’s the consequence? It’s a light bulb. I can turn your light on and off - but so what? It’s annoying but I can unplug it and call the company who installed it to have them fix it. But that very smart device may be the step that the hacker takes to get into your home. So maybe it’s a smart light bulb that uses Bluetooth or Wi-Fi or ZigBee or Z-Wave and someone outside can connect directly to your light bulb and can use that as a step to your light controller and then from your light controller to your Wi-Fi router. And once they have that, they have everything. Once I have your router I can intercept all of your traffic. Everything. Your banking details, your passwords. So the risk is not to the device, be it a light bulb or a thermostat, it’s the systems that it can lead to. If that device is insecure, that’s the way in to the rich pickings on your network.

LED professional: Since they can take over your equipment and everything on your network, is it possible for them to mimic you by stealing your identity to harm others?

Ken Munro: Potentially, yes. Your light bulb might be the way into the hub that controls it. One hub could then be used to attack other hubs in different houses around the world. So actually, you become the source of the vulnerability even though it’s the manufacturer’s fault for not writing the software properly. So the police officer then knocks on your door because it was traced back to your IP address. And what’s your defense against that? How do you prove it wasn’t you given the log on your Wi-Fi router says it was you.

The next point I want to make is about installers. The product may well be secure and the manufacturer will issue a guide to ensure correct installation. The instructions for the installer might provide a process to follow together with a caveat from the manufacturer that states if this advice is not followed, it renders the product insecure. We often find instances where installers have failed to follow that advice with IoT equipment resulting in a vulnerable device that is then just waiting to be compromised. So I strongly advise everyone, whether they are an installer or a manufacturer, to make sure installers are trained. Make sure you have a verification system to ensure the product is securely installed because otherwise it will be the manufacturer’s reputation and/or the installer’s reputation placed on the line and the consumer’s data that will be exposed.

LED professional: During your career, have you recognized similarities between product groups? Are there product groups that are more secure than others?

Ken Munro: It depends on the history of the device and where you find it in its life cycle. Some products, such as industrial controllers, started becoming more secure, ten to fifteen years ago, when the audit process gained momentum, so in many areas security has improved. But each time a new product group comes to market, we see a new set of security flaws. We did a lot of work on smart TV’s and discovered they were listening to you speak but now audio controls are vastly improved. But there are inevitably exceptions to the rule. If you look at Building Management Systems (BMS), we continue to find security flaws there. The last few years has seen innovation in smart lighting take off and it’s this drive to be first to market that can see security sacrificed. For that reason, it’s very important that you can fix your product when it is on the market using Over the Air (OTA) updates.

LED professional: Is there a relationship between the price of a product and how secure it is?

Ken Munro: We carried out extensive research last year to see if there was a relationship between an expensive product and good security. Perhaps surprisingly we found it was random. So you can buy an expensive product with terrible security or a very cheap Chinese copy that has better security. Generally speaking you’d make the assumption that an expensive product with a high build quality or used for industrial purposes would be good but actually there is no correlation between price and security which makes it impossible to tell without testing. That’s why industry regulators are now looking to push Kitemarks [I] to incentivize manufacturers to invest in security and to help users differentiate and flex their buying muscle.

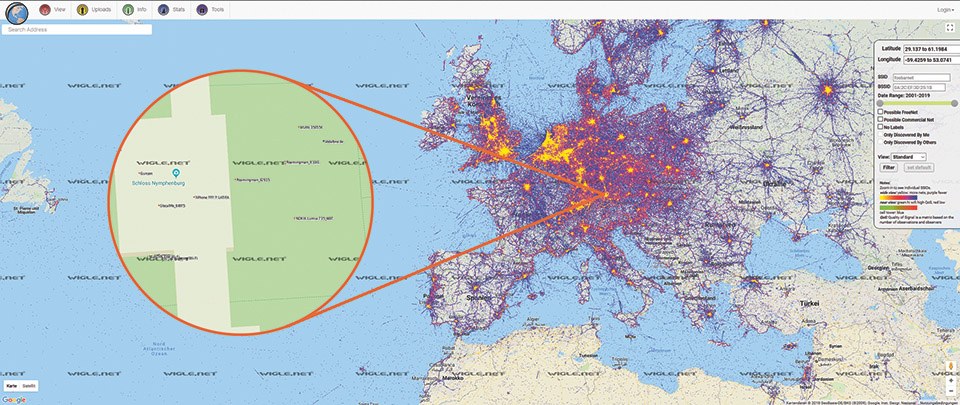

A lot of information about accessible networks can be found easily on the internet. For instance, wigle.net shows wireless hotspots that make people aware of the need for security when running a wireless network. With a little detailed knowledge the information can be used for hacking unsecured hotspots or products

A lot of information about accessible networks can be found easily on the internet. For instance, wigle.net shows wireless hotspots that make people aware of the need for security when running a wireless network. With a little detailed knowledge the information can be used for hacking unsecured hotspots or products

LED professional: Are there differences in the security levels when it comes to Bluetooth, ZigBee, etc.?

Ken Munro: All the ones we’ve mentioned: Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, BLE, ZigBee, Z-Wave - they all have good support for security. The problem is that often the manufacturer doesn’t implement the security. We have just finished some research around Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) and one of the most common problems is not setting up the connection securely. BLE has support for strong pairing and strong cryptography and bonding. It’s very secure and very difficult to crack. But most manufacturers simply offer a connection with no security at all. No PIN, no encryption, nothing! In all the products that we have tested, we’ve never seen BLE used to create a bond. Even though the functionality is there, manufacturers don’t use it.

LED professional: One of the new systems is LiFi. Do you have any experience with it?

Ken Munro: We haven’t looked at LiFi yet. That’s next. But Wi-Fi, for example, has fantastic support for security and encryption and everyone uses WPA, WPA2. But there is a fundamental flaw in use and that is that everyone leaves their Wi-Fi chip set on their mobile phone “on”.

I did a survey in London for Sky News last week and we showed this problem is endemic. The London Underground is doing a trial right now to gather useful data from travelers to establish how they should schedule their trains and how they should direct people but if they wished, they could also track individuals. So I could tell you exactly where you were at any point in time just by virtue of your mobile phone Wi-Fi.

![There are a number of security solutions available on the market now. Consequent use of them can significantly reduce the risk of being hacked (Credits: Infineon [2] There are a number of security solutions available on the market now. Consequent use of them can significantly reduce the risk of being hacked (Credits: Infineon [2]](https://www.led-professional.com/media/resources-1_articles_tech-talks-bregenz-ken-munro-partner-founder-pen-test-partners_security-solutions-for-iot-devices-infineon-original-there-are-a-number-of.jpg/@@images/image-1280-b3a3a95ba9796332d8d6b3097827c923.jpeg) There are a number of security solutions available on the market now. Consequent use of them can significantly reduce the risk of being hacked (Credits: Infineon [2]

There are a number of security solutions available on the market now. Consequent use of them can significantly reduce the risk of being hacked (Credits: Infineon [2]

LED professional: So in the end, everybody is responsible for his or her own security?

Ken Munro: Yes, make sure you set strong passwords, use a password manager if you’re a consumer or you’re working in business, and if you use social networks, use Two-Factor Authentication (2FA - that’s where an SMS message is sent to your phone to check it is you logging in). Even better, use a source called “Authenticator App” which sends a message to an app on your phone which only you can verify.

LED professional: So if you have one insecure device it can be like an open door and lead the way to other connected devices? Is every device in the house a threat?

Ken Munro: That should not be the case if these devices are configured by the user or installed by a technician correctly. Yes it takes a little bit longer to do but it will then prevent the type of scenario you’re describing. Unfortunately, the tendency is to just plug-and-play. As users we assume that if it works, it’s fine. But one device can compromise others. Voice control is a good example of that in the form of Voice Activated Assistants such as Alexa.

LED professional: Can we talk about Alexa?

Ken Munro: Alexa itself is fairly secure. It’s always listening, of course, but is fairly secure. The problem is that many people then integrate Alexa with their products either wrongly or without considering the security implications. It’s one thing to say “Alexa, turn on the lights” but it’s another thing to say “Alexa, unlock my door.” What’s to stop a criminal outside your house shouting through your window and walking in? There are other silly consequences - the radio show that saw residences up and down the country ordering a doll’s house springs to mind - so it’s very important that manufacturers think about the potential negative impact of using voice control.

LED professional: There is an old story about a company that made classic mechanical locks which then they hired a former criminal to open the doors to test the locks.

Ken Munro: That’s exactly how ethical hacking works. We will reverse engineer your technology, take the chips apart, inspect the contents of the chips, find the firmware running on the chip and establish all the ways a hacker could potentially compromise your system.

LED professional: I remember that you said there are a lot of opportunities on the hardware level, not just the software level?

Ken Munro: Yes, this is the game changer with IoT devices. In the past, when we were just focused on mobile apps it was fine. You owned the server. It was your data center and you had control. But now with the IoT, you’re putting your hardware in the hands of not just the consumer but also the hacker. You’re giving them time to explore and dismantle that product to establish its vulnerabilities. To survive that, your hardware security has to be excellent and robust, using obfuscation to fool the hacker or tamper-proof components. Sadly, that’s rare. We use logic probes and analyzers and find weaknesses in the chip, the firmware and the software and, if we extract your firmware, we gain access to your secret keys and your passwords. LED professional: Is there a difference between products in the private and professional sectors?

Ken Munro: It’s random, again. Of course, there are many more products on the market for the consumer than there are in the business area. But what we find so often is that when you buy a corporate product, industrial grade and you plug it into your network for your elevators, your lights or your ventilation, that creates a back door.

LED professional: What can the consumer do? I know that you said we need strong passwords, etc. but if I buy a light bulb, I don’t usually need a password.

Ken Munro: There is nothing you can do as there are no standards although we are starting to see regulations emerge. The U.S. senate has drafted an IoT security bill and the EU is doing some work at the moment but there’s still a long way to go. In the UK, we’ve seen the DCMS (Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport) release its Secure by Design guidelines which are a first draft. In principle, this is to be welcomed and it does allude to a Kitemark called Trustmark for home-based devices. But there’s a lack of teeth to the standard with no talk of enforcement.

LED professional: What future developments do you see and what general advice do you have for the industry?

Ken Munro: Manufacturers and installers need to ask questions about security. So often, a manufacturer will have an idea, they’ll make a product, they’ll send it to manufacturing and then it will go to market. No-one during the process has stopped to ask about security. If the question was asked early on in the development process we’d see manufacturers look for advice, seek assistance in secure app design, ask the hosting company about how data is protected, and the hardware manufacturer about physical security. But if it’s asked too late, everyone is caught on the backfoot. Manufacturer’s turn a deaf ear to disclosure. Consumers are the last to know they’ve been exposed. So the one piece of advice I’d give the installer is ask your manufacturer about security. Ask their specification. Ask for their installer security guide. And to the manufacturer ask the security question early and anticipate how you will support that product. Ask your suppliers about security. Do that and you’ll have a secure product and I won’t be hacking it.

LED professional: Do you have any idea about security costs? If you develop a bulb with IoT capabilities and you do all the things you just suggested, how much of the development costs will go towards security?

Ken Munro: It shouldn’t be significant because when you specify your development, you should be asking the security question and stating the device should comply with standards X,Y, Z. OWASP (The Open Web Application Security Project) has some great standards for mobile apps, web apps and API’s. And if you have it in your contract that the product should comply with these standards and then it doesn’t you just say “I’m not paying you” so maybe it’s cheaper!

The cost for security should be marginal if you ask the question about security early enough. Research from Gemalto [1] suggests that 9 percent of IoT vendor budgets are spent on security. Security gets expensive when you try to do it at the last minute. Trying to retrofit security is very difficult and very expensive. I would also seriously think about what the impact is on your brand if your product is hacked. What if my product is the source of a Denial of Service attack? What about the liability of my product? Think about bad exposure, bad public relations, bad marketing, and think about lack of sales. Remember that security is a bit of an insurance policy. It’s making sure you are not an Equifax, for example.

LED professional: So every development company should add it to their project management guidelines?

Ken Munro: Absolutely.

LED professional: Thank you very much for your time.

Ken Munro: Thank you.

At LpS 2017 Ken’s enthusiasm for his work shone through in a talk that was both informative and fun to watch

At LpS 2017 Ken’s enthusiasm for his work shone through in a talk that was both informative and fun to watch

Ken Munro's short CV:

Ken Munro is a regular speaker at the ISSA Dragon’s Den, (ISC)2 Chapter events and CREST events, where he sits on the board. He’s also an Executive Member of the Internet of Things Security Forum and spoke out on IoT security design flaws at the forum’s inaugural event. He’s also not averse to getting deeply techie either, regularly participating in hacking challenges and demos at Black Hat, 44CON, DefCon and Bsides amongst others. Ken and his team at Pen Test Partners have hacked everything from keyless cars and a range of IoT devices, from wearable tech to children’s toys and smart home control systems. This has gained him notoriety among the national press, leading to regular appearances on BBC TV and BBC News online as well as the broadsheet press. He’s also a regular contributor to industry magazines, penning articles for the legal, security, insurance, oil and gas, and manufacturing press.

Notes:

[I] The Kitemark is a UK product and service quality certification mark

which is owned and operated by The British Standards Institution

(BSI Group). The Kitemark is most frequently used to identify products

where safety is paramount, such as crash helmets, smoke alarms and

flood defenses.

References:

[1] Gemalto & The Breach Level Index: www.gemalto.com |

breachlevelindex.com

[2] Infineon IoT Security Website: www.infineon.com/IoT-Security