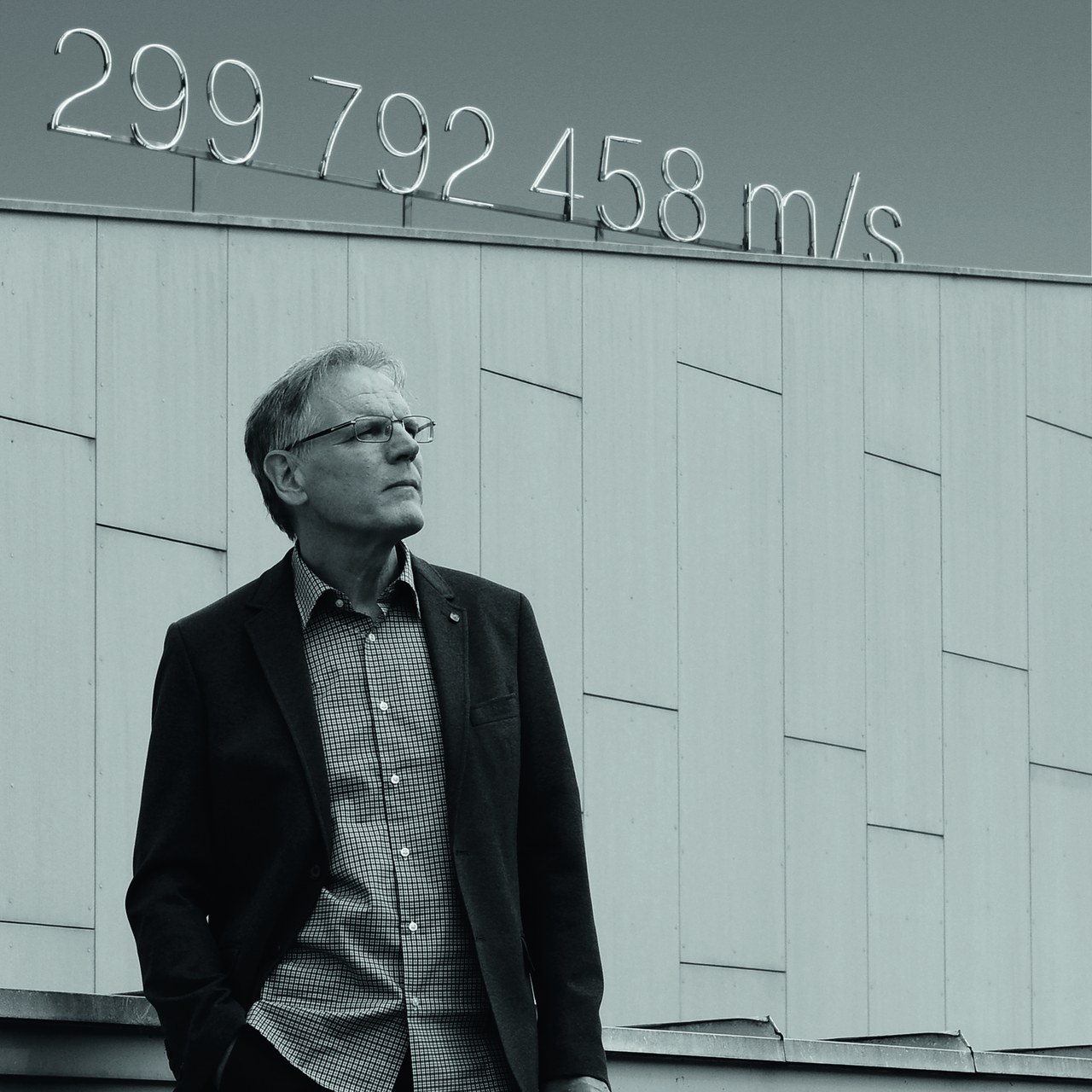

Tech-Talks BREGENZ - Dr. Wilfried Pohl, Research Director, Bartenbach GmbH

Bartenbach is one of the pioneers in light planning and lighting research. Since Christian Bartenbach Senior founded the engineering office in 1976, the company has been dedicated to light and visual perception. Several lighting inventions made over the years, can be attributed to Bartenbach. Dr. Wilfried Pohl, as a member of the Managing Board and Director of Research at Bartenbach GmbH, has played a substantial role in many developments. LED professional talked with him about Bartenbach’s history, education in the lighting business, the lighting parameters he deems very important, the quality of light, "Human Centric Lighting" and "Biodynamic Lighting“, and how LEDs have changed the light planning and lighting research company, in general.

LED professional: First of all, we’d like to express our appreciation for taking the time to come to Bregenz for this interview.

Wilfried Pohl: Glad to be here.

LED professional: To start, could you tell us a little about Bartenbach? How did it come to be? How has it developed? What is Bartenbach’s current position?

Wilfried Pohl: Bartenbach is an engineering office, founded by Christian Bartenbach. Our founder, who is now 87 years old, turned over the business administration to his son, Christian Bartenbach Jr. in the year 2007.

Light interested Christian Bartenbach Senior from an early age and as a young man he made contact with a group of psychologists that were interested in light and visual perception. It fascinated him to such a degree that he decided to open a light planning office. That was in the year 1976, when light planning offices were few and far between and light planning was considered exotic.

LED professional: How was he able to finance the company?

Wilfried Pohl: From the beginning, Christian Bartenbach’s goal was to find architects and building contractors that were agreeable to the concept that good light planning was a necessity. Architects were especially open to this idea because they saw light planning as a defining characteristic that they could use. Everything was financed through the light planning contracts. Through the planning orders it was possible to constantly develop new luminaires that were designed to accommodate the special performance requirements of the projects.

LED professional: Could you give us a couple of examples of the special luminaires?

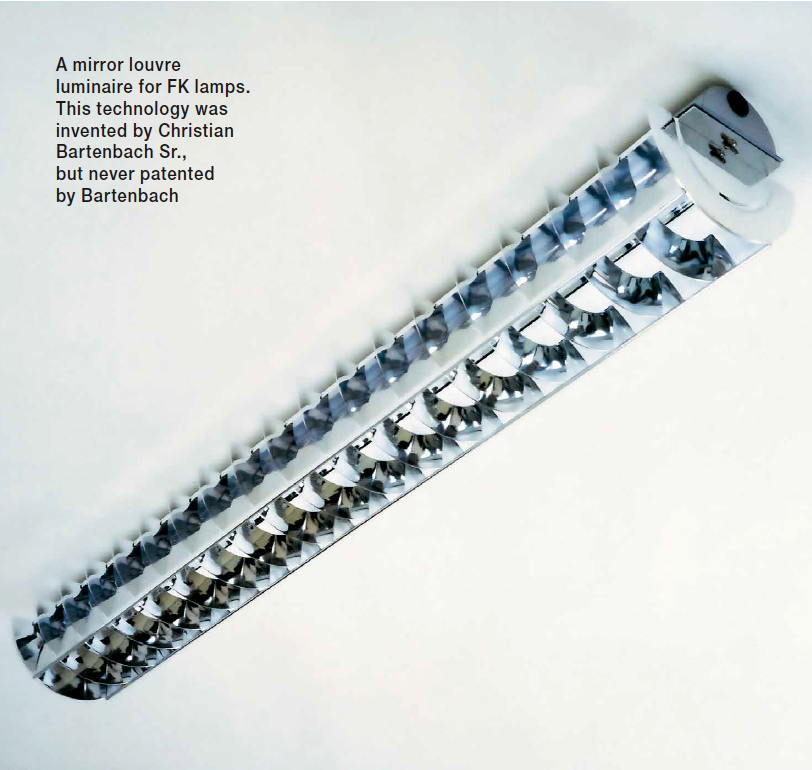

Wilfried Pohl: Bartenbach Senior was, for example, the inventor of the mirror louvre luminaire. Even though the fluorescent lamps in those days (I’m referring to the old T12 lamps), had moderate luminance, he decided to shield the lamps in order to avoid psychological glaring. The mirror louvre luminaires were never patented by Bartenbach, which meant that he missed the chance for licensing them and earning a lot of money. Within a very short period of time every luminaire manufacturer started producing them. And that’s how that technology became the conventional office solution.

LED professional: Were these luminaires produced by Bartenbach?

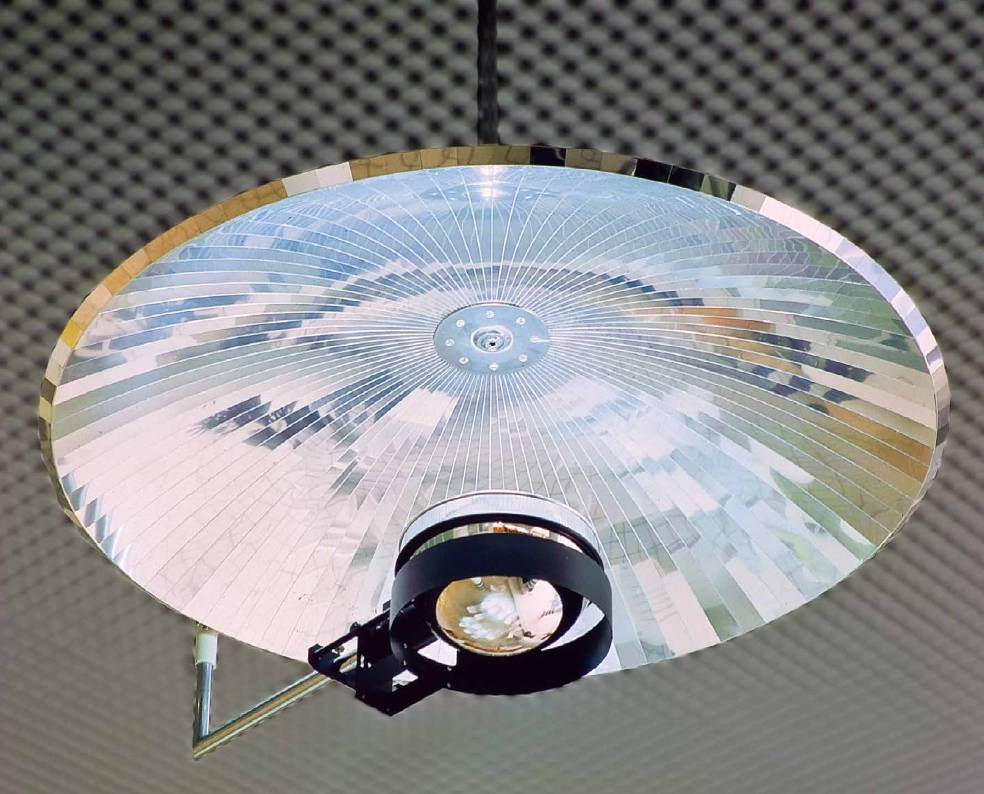

Wilfried Pohl: No, the luminaires developed by Bartenbach were always included in the tender and manufactured by the supplier. Of course this caught the attention of the luminaire manufacturers because they were always looking for innovations, and very often they included them in their catalogues as a serial product. Another development was the secondary reflector technique, where the lamp couldn’t be looked at directly from any angle.

Bartenbach was one of the first to design secondary luminaire systems to prevent a direct view of the lamp and reduce glare

Bartenbach was one of the first to design secondary luminaire systems to prevent a direct view of the lamp and reduce glare

LED professional: And Bartenbach was able to finance the development of all these new systems?

Wilfried Pohl: Yes, it was all financed through the planning. In those days, building contractors were willing to pay for the analyses of the benefits of a new solution as well. We received additional contracts for luminaire developments and, of course, for our analyses in the context. Later on, that stopped. The market changed and around 1995 research couldn’t be financed like that anymore. Building contractors were less and less apt to take part in that type of adventure in the course of a building project - and research and development as part of a construction project is always an adventure. You are always encountering unexpected problems that have to be solved.

LED professional: What were Bartenbach’s key arguments that would convince the client to hire you?

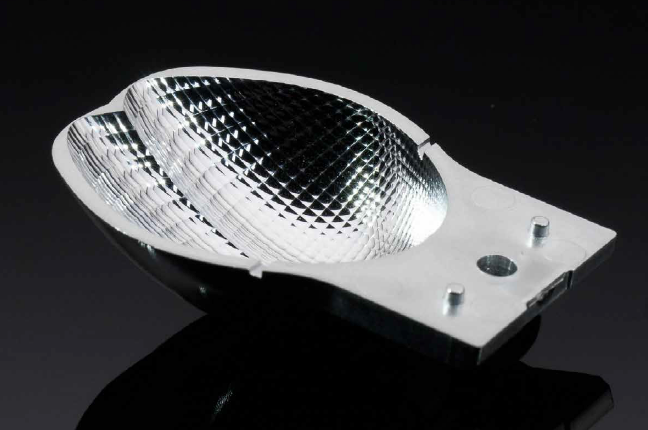

Wilfried Pohl: One key argument was the quality of lighting. Those were the days of the first screens. Bartenbach carried out intensive studies, where computer screen work stations had been set up, the surrounding brightness was varied, and the screen luminance were adjusted. With the results you could plan lighting systems that could increase the visual performance significantly, e.g. reduce the frequency of mistakes made and decrease mental strain, etc. But to get back to the story, from 1995 on, the R&D department became its own profit center and has had to support itself. We develop, for example, optical components that are sold independently of our planning projects. In the meantime we have about 10 employees that work solely on optical design. The optical designs are developed and then licensed. Today a lot of companies manufacture products that were developed by Bartenbach, mainly in Europe, but also in India, America, to name a few.

LED professional: Could you tell us a little about the Lighting Academy?

Wilfried Pohl: The Academy was started in 2003. An academically recognized, 2-year master course was established. Through the training course, Bartenbach was able to acquire a lot of good people, but especially important was the fact that we were able to anchor light consciousness in the mindset of society and of many international companies through the graduates that work all over the world. The course used an enormous amount of resources at Bartenbach and even though there was a significant tuition, it wasn’t self-financing. Because of that, new management thought it best to discontinue the master course in 2015.

LED professional: I’d like to talk about the subject of research. You started out with conventional light sources and did research in this area. About 15 years ago, the gradual change over to LED began. How did this new technology influence the focus of your research?

An “artificial sky” allows daylight simulation and research using true scale models

An “artificial sky” allows daylight simulation and research using true scale models

Wilfried Pohl: Our research has two focal points. On the one hand, the area of perception and light impacts, and on the other hand, we do research in the area of technology. This includes calculation and simulation programs, new materials, energy efficient buildings and daylight. But the LED completely shifted the focus of our research in the area of artificial light. Bartenbach Senior again proved his farsightedness by equipping a meeting room with LEDs in the year 2000. At that time the LEDs had a power of 0.1 Watts and a light flux of 1 lumen. In hindsight, I have to say that it was the right decision. At that time, even though the LED was being intensively publicized, not many building contractors were working with it, and for those that did, the cost of learning was high. The quality of the lighting wasn’t right, energy savings were minimal and the LED’s including the drivers very often broke down after a couple of years. But because of our early start we were able to acquire a proportionate lead.

LED professional: And are there light effect research subjects that have evolved through the LED that didn’t play an important role before?

Wilfried Pohl: I would say that the subjects have come up again. Many of the problems that early illuminants had have surfaced again with the LED. I can remember that the subjects of high luminance, photobiological safety, glare and UV were being discussed intensely in the year 1985 in regards to the upcoming metal halide lamp. And those are the topics that are being discussed again in regards to the LED because the LED has already surpassed the metal halide lamp in relation to luminance. Photobiological safety must also be taken seriously. During the last few years it hasn’t been relevant for research but in the meantime it has gained a significant amount of importance.

LED professional: Isn’t blue light hazard a subject in regards to LED? Have you examined it? It keeps coming up as a topic for discussion but no one really knows how to classify it.

Wilfried Pohl: Yes, it is indeed a topic. Although I have to say that the blue light of an LED is no bluer than earlier illuminants. But our studies are mostly on glare, which is the more harmless topic area, but the threshold is much lower here. If you avoid glare, there’s no danger for the eyes. Generally, I have to install the illuminant so that the radiation is never in the viewing direction.

LED professional: How important is the subject of energy efficiency for Bartenbach?

Wilfried Pohl: Although lighting quality rather than energy was the focus in the past that has changed over the last few years. Today we can also argue that you can save energy through a combination of daylight and artificial light. But the deciding point is still the quality of light. For example, one of the main things that needs to be done when you are using daylight in the building is to avoid glare. As an example, in this room we’re in I would guess that we have a sky luminance of a few thousand cd/m2 at the window and here at the table about 80 or 100 cd/m2. That is a ratio of about 1:50 and it’s not that easy to cope with if visual performance is necessary. But light also has an emotional quality and that’s why a view through the window is important. So it has to be decided whether I want to look out the window and enjoy the view or if I have to work on a computer screen.

LED professional: Theoretically speaking, can you underpin something like that?

Wilfried Pohl: Yes. On that score we have developed a visual perception concept. We based it on a PhD study from Schumacher, who measured contrast sensitivity with various background brightness. The question is, how much of a contrast does there have to be, for example, between a letter and the paper in order for it to be seen. The threshold of visibility depends on the surrounding brightness. If it is too bright, the contrast sensitivity decreases dramatically, which means that it becomes more difficult to see and read the letters.

LED professional: But how do you find common ground between these quality requirements? On the one hand, I have to reduce the light intensity from the window, dim it, in order to avoid glare and to fulfill the visual task. On the other hand, I have lost my view of the outside and this demotivates me because I feel like I’m locked in.

Wilfried Pohl: That is the real challenge - to be able to deal with these contradictions. There is not one single solution that is right for every case. If you are very concentrated on your work, the surroundings don’t play a role, but in phases when you are less concentrated, the view is more important. You could use a controllable system where the user can decide but the user can’t decide everything, he also needs the support of the controls.

LED professional: After so much research, are there hard facts available today? Do we know what the effects of a flawed light situation is in comparison to an optimized light situation? Are the figures available that confirm the reduction of sick days or higher efficiency?

Wilfried Pohl: There are a large number of studies but the results are mostly vague. And they’ll always be weak. People’s health is dependent on so many things that it just isn’t possible to determine an unambiguous cause-and-effect relation. It’s more a question of proving the evidence. Bartenbach also had the idea of measuring physiological data. Earlier, all the studies were made with questionnaires, and you don’t get hard facts from questionnaires, .

LED professional: What physiological data can be compiled in order to receive objective statements?

Wilfried Pohl: For example, the conductivity of the skin, which is a stress indicator, was measured. If you are under stress, you begin to sweat, the skin becomes damp and conductivity increases. Later we measured heart rate variability, but interpreting that data is difficult. A small amount of variability means that you are tense and a larger amount of variability means you feel more comfortable. But a detailed interpretation of the data isn’t as unambiguous. Dr. Pohl talked about the combined use of daylight and artificial light in buildings with Siegfried Luger and Dr. Sejkora in a typical meeting room with an estimated luminace of 80-100 cd/m2 at the table and a sky luminance of a few thousand cd/m2 at the window

Dr. Pohl talked about the combined use of daylight and artificial light in buildings with Siegfried Luger and Dr. Sejkora in a typical meeting room with an estimated luminace of 80-100 cd/m2 at the table and a sky luminance of a few thousand cd/m2 at the window

LED professional: Research is very expensive. How does Bartenbach finance things like perception studies?

Wilfried Pohl: We submitted our first EU funded project proposal in 1997. Besides the EU, the Republic of Austria was also a strong supporter of our research. We usually have 20 to 30 research projects running at one time and many of them are funded. On the other side, we sell many of our perception studies and finance ourselves with that money. Amongst others, our clients are large corporations who need some basics in these fields. The development of optics for LED luminaires - like this tiny IP protected free-form optics - is one of the company’s main business branches

The development of optics for LED luminaires - like this tiny IP protected free-form optics - is one of the company’s main business branches

LED professional: We were talking earlier about glare. It has always been Bartenbach’s opinion that artificial light should narrow beam with sharp cut-off in order to avoid glare. Is that a guiding principle for planning in every respect?

Wilfried Pohl: I think that with certain applications you have to change your way of thinking. Systems with a sharp cut-off can cause “light pressure” and the necessary vertical illumination has to be created in a different manner by using the surfaces in the room. The walls have to be targeted with wall washers. At the end, every point of the room needs, what I call, a balanced radiation field.

LED professional: That sounds like a very complicated solution. What alternatives are available?

Wilfried Pohl: Yes, these lighting solutions have to be planned very carefully. You can also make the luminaire with a larger and diffuse light outlet area and get away from the point light source. Due to the resulting glare and uncontrolled light distribution that used to be taboo for us. Indirect lighting was developed 30 years ago, and later came mellow light. It’s clear that a luminaire that emits diffuse light will create glare, but you have to ask yourself how big the disturbing effects will be. Even a narrow beam downlight without any glare in the viewing directions has its disadvantages. We, at Bartenbach are in the process of discussing this and changing our way of thinking.

LED professional: So you’re talking about a solution with shielded direct light and diffuse share?

Wilfried Pohl: Yes, but you have to keep the high luminance of the LED in mind. Especially the future technological development with semiconductor lasers - if you look at the beam, you’ll be blinded. Here you will have to think carefully about how to use the laser light sources. The question is whether or not we can implement it into general lighting.

LED professional: At first everyone appreciated the LED because we finally had a point light source available. Now, the trend seems to be that we’re moving towards mid power LEDs and we’re trying to make surface light out of the numerous small point light sources. Is that a sensible use of LEDs?

Wilfried Pohl: Actually, it has always been my opinion that that is absurd. We now have a point light source with high brilliance. Perhaps just a word about brilliance. If I look at a surface, it always has a certain amount of gloss and a structure. It makes a very big difference if I shine a point light source or a diffuse light on it. The surface has a completely different look and feel. Depending on the use, I need a mixture of brilliant light and diffuse light. The LED is a wonderful substitute for the light bulb because it also creates brilliant light. And we need that. But we also need diffused light. You can make it with indirect lighting - and that’s how we do it. But it is certainly also ok to line up a lot of low power LEDs behind a diffuser. In any case, I shouldn’t use a high power LED for it.

LED professional: Do you have, for example, OLEDs in mind? Would that be a suitable source for the diffused part?

Wilfried Pohl: It seems to me that things have quieted down quite a bit lately when it comes to the OLED. At the beginning we worked on research projects but in the last while, there isn’t much going on. Evidently the OLED failed because of technological problems, especially when it came to mass production. Actually, the OLED would complement the LED perfectly. That way we could combine a high quality surface light source with a brilliant point light source. Unfortunately the OLED has technological problems and the consequence is that it is much too expensive.

LED professional: How much is known about biological light effects today and how is it taking into account during the planning stage?

Wilfried Pohl: The future of light depends on quality. And biological quality is a part of that. We have the technology to do whatever we want with the LED with a high degree of energy efficiency. But there aren’t metrics for the concepts I talked about earlier, not only for biological qualities, but even for visual qualities, e.g. like brilliance or radiation field. I can’t measure brilliance and there aren’t any quality criteria for it. Another example are the risks of LED lighting.

E.g. how we deal with photobiological safety is inadequate and must be regulated. The norm EN62471 leaves a lot of things open, contradicts itself in some parts and has technological mistakes. Many metrics are missing for visual evaluation or they are outdated. In regards to spectral quality, many steps need to be taken and a lot has to be updated. We need to make lighting quality measurable.

When we talk about biological effects, we find that there are no rules. Today, if we want to achieve biological effects, we start from vertical illuminance at the eye. But if we think it through, we arrive at completely different requirements from those we used to have. We always planned for horizontal illuminances and now we find ourselves with an evaluation that is oriented on humans and requires vertical illuminance. How can I generate biologically effective light at a desk? How can I generate 1,000 lux near the eye without creating glare? Physically, it’s just not possible. And this dilemma is just going to get worse in the future because we’ll need even higher illuminances near the eye.

Human Centric Lighting is one of the trends in the lighting industry. Biodynamic lighting would probably be the more accurate way to describe scenarios like this one: Part of Bartenbach’s office in the late afternoon illuminated with 2700 K (left) and 4000 K (right). The effect on people is one question Bartenbach strives to answer with their perception studies

Human Centric Lighting is one of the trends in the lighting industry. Biodynamic lighting would probably be the more accurate way to describe scenarios like this one: Part of Bartenbach’s office in the late afternoon illuminated with 2700 K (left) and 4000 K (right). The effect on people is one question Bartenbach strives to answer with their perception studies

LED professional: That means that what we have made up until now has been wrong and what we’re doing is contradictory. Isn’t that a big problem?

Wilfried Pohl: You can see it as a problem or as a chance. We are working on completely new concepts to find solutions. We have to find a way for the luminaire to blend into the surrounding luminance and then it can’t cause glare. At the same time we have to achieve high illuminance near the eye, and I can only achieve that through the surface areas of the room. That means that it will become increasingly important for the room to be used as a reflector and to include the surfaces in the room in the planning stage. Otherwise there is no chance to achieve a biologically effective amount of light at the eye. We call it the “integrated concept” and it gives us the chance to push lighting design, which is our service, to the forefront. In addition, it is also the chance to develop new concepts and new luminaires.

LED professional: What would these types of light solutions look like?

Wilfried Pohl: There are a few different approaches. Bartenbach, for example, would propose a solution that integrates the entire room. Of course, that would be complicated, but from our point of view, it would be the best way to achieve all the requirements. Another might just put a floor lamp in the room and claim that the biological effect has been achieved. And another person would use a desk lamp. And if they claim that they are making Human Centric Lighting (HCL), I don’t think it would be very plausible. But nevertheless we think that the future lies in “biodynamic light”. That’s light with corresponding controls and intelligence that is tunable regarding color temperature, intensity and distribution.

LED professional: How much is Bartenbach affected by the subject of Smart Lighting?

Wilfried Pohl: There is a point of contact there. Of course we are keeping our eye on what is happening on the market and we know the state of the art. But if we want to make biodynamic light, we are aware of the fact that the different proprietary systems are unable to cope. There are enormous implementation problems; certain control and regulation requirements that aren’t supported by the systems.

LED professional: You mentioned biodynamic light and variable light color. Generally, we only think about the color temperature. How important is the actual spectral distribution?

Wilfried Pohl: I believe that for spectral quality the actual power distribution is also important. Of course we are now at a high level, but in regards to color rendering, there is still room for improvement. But the metrics will have to be adjusted so that a proportionate improvement potential can be described. LEDs, especially, have certain differences that cannot be quantified with current metrics. Researchers agree that there is also room for improvement when it comes to the “whiteness” of light. It is also possible to achieve some improvements in regards to the biological effects by optimizing the spectral distribution at the same color temperature. Summarizing, the spectral quality must be describable with additional coefficients and not through color temperature and color rendering alone.

LED professional: In connection to HCL we hear a lot about the biological effect of light. What do we know about that, exactly?

Wilfried Pohl: The hardest facts that we know today describe the nightly suppression of melatonin. Melatonin dumping was measured from the pineal gland. In the dark, at night, it has a constant, high value. If the test person is subjected to light, the release of melatonin sinks to almost zero within minutes. The effectiveness is proven for nighttime but there aren’t any hard facts for the daytime.

LED professional: Does that mean that if I work at night, or drive a car, I need to be proportionately lit up in order to suppress the release of melatonin and not get tired?

Wilfried Pohl: For a long time, that’s what we thought. Today, the opinion is rather that we have to be careful with melatonin suppression. Medical practitioners are of the opinion that the nightly suppression of melatonin can promote cancer. In the US, they have even gone so far as to warn people about the use of LEDs. And chronobiologists agree that we should disturb the biological clock as little as possible with light. So the common approach now is that we should use light at night in a way that avoids melatonin suppression as much as possible. We have carried out studies in which we proved that the use of light with a lower color temperature (we went down to 1700 K in our study), doesn’t block melatonin. Today we go up to 2200 K - that’s enough and it is a lot more comfortable. Our study also showed that despite the absence of melatonin, concentration was not reduced.

LED professional: Bartenbach will be running a workshop on the subject of “Visual Perception” at the TiL 2017 in Bregenz. What can you tell us about this workshop?

Wilfried Pohl: It is a great chance to display and demonstrate some of our insights. We are hoping to inspire people with a few suggestions for completely new lighting concepts. We want to sensitize people to the subject and start discussions. In contrast to what we did a few years ago at the LpS, we not only want to talk about visual effects but we are also going to focus on biological effects and Human Centric Lighting.

LED professional: Thank you again for making the time to come to Bregenz and for this interesting interview. We appreciate it.

Wilfried Pohl: My pleasure.

Wilfried Pohl

He studied mathematics and physics. He has been a member of the Managing Board and the Director of Research at Bartenbach since 1998. He deals with daylighting and artificial lighting, the development of (artificial and day) lighting devices, optical design, photometrical and thermal measurements, calculation and simulation tools, lighting fundamentals, building physics (in connection with day lighting, sun protection, cooling and heating), visual perception and light and health. He was the leader of diverse international planning and R&D projects in these fields. He has published numerous scientific publications and is a lecturer at various universities.

(c) Luger Research e.U. - 2017